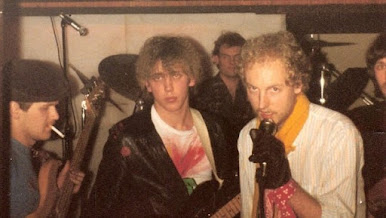

In all honesty, our first efforts were absolute rubbish, but we were 100% committed to the idea of forming a Punk band. By January, I'd driven my parents mad. We would sit up every night, writing songs, making a racket. I was at Orange Hill School and I made several friends in decent bands. All had the same problem, nowhere to practice and a lack of equipment. Many had guitars, few could afford amps, no one could afford a PA system, necessary to amplify vocals. In early February 1979, my Dad came up with a solution. The caretakers cottage at the industrial estate he had acquired had a derelict caretakers cottage. He offered to rent it to me for band rehersals for £5 a week, on the condition, I didn't play music at home, as he was at his wits end with all of the visitors and the racket. This was beyond my wildest dreams. All we had to do was secure it. There was a coin operated electric meter. We simply got corrugated iron and boarded up all of the windows. Old sofas and mattresses were acquired, I proposed to a couple of other bands we have a loose collective, they left their gear at the studio and got a night a week, for a small contribution to the rent. It became a social hub for local teenagers to hang out and play music. It was overrun with vermin and smelled of damp, but it was like a mythical promised land of punk rock music and freedom. We had a launch party on the 14th February 1979, and in November, we had our first paying customer, The Polecats. Soon the other partners in the collective had moved on. For me, it was a source of beer money through my school years. I had a simple formula. I invested 50% of the profits in equipment and spent 50% on enjoying myself.

Back in 1979, Mill Hill was like a desert for teenagers who loved music. The nearest we got to a music venue was the Jukebox at the Three Hammers. I was determined to change that and in January 1980, I organised a gig for local bands at the Union Church, Harwood Hall. It was packed and after the bands were paid, I had enough money to take my mates out for a slap up curry and beers, with cash to spare. Another couple of gigs happened there, before an idiot let off a fire extinguisher in the toilets and we were banned. I was furious, but there was nothing I could do to persuade the Church that we'd ensure it didn't happen again. I learned that you need proper security at events where there are young people.

By the end of 1980, I'd learned that you could earn a living in the music business if you worked hard and were prepared to take risks. I also realised that there was a huge market for space for people to play music. I had a vision of what I wanted, but everyone else laughed in a rather patronising fashion. Despite the fact we had made a small scale profitable business from nothing in no time at all, no one would lend me money and no one believed it was anything more than a passing fad.

To the consternation of my parents, when I finished school, with poor A level grades, I didn't get a job. I moved to Stockholm to try and get my band a tour and to take stock. The tour was arranged. If I'd had a bit more business experience, we could have made a tidy profit and secured a musical future, as it was I ran up a huge debt with dodgy geezers, the only people who would lend me the cash. To remove that albatross, I got an IT job, the most high paying I could.

But the dream of a studio wasn't dead. The band were still playing and evolving. In 1991, I received a redundancy payment from BACS, where I was working as an IT developer. This allowed me to buy my former partners out of the studio business. I decreed that I would work freelance in future, and recruited Ernie Ferebee, a friend from the security industry as my new partner. We worked tirelessly to build the studio up. Between 1994 and 2000, we went from having two small studios to having ten, a recording studio, a music hire business and a shop.

But our ethos was different to the rest of the London music industry. I wanted to keep the punk rock ethos of being self sufficient, getting people playing and keeping costs low. Our studios were designed to be functional. We wanted to get people in who had previously thought studios were too expensive or too elite. In our complex, we decided that studio ten would be the cheapest in London and would be fully equipped. We would not be beaten on price. To attract young bands, we offered off peak rates that were so cheap we lost money on them. That sounds like madness, but my view was the other studios would subsidise it. Initially that caused problems, as we tried to limit it to students and the unemployed, but people would lie and we'd have arguments. To my amazement, due to its incredibly high utilisation, it actually was as profitable as the other studios. We reacted by increasing our off peak slots and getting cheaper, simpler equipment in many rooms.

One of the most amusing incidents occurred when a competitor booked in to use a studio to work out our formula. The guy sneered at the equipment, sneered at the basic facilities and told Ernie that we were a bunch of comedians who would soon go broke, as no one would pay to use such rubbish. Ernie, who was 6'6 and came from a family of East End Bare Knuckle boxers was livid, but I walked in before he thumped the guy and said "Come back in five years time and say that". One of our regulars told us that he'd rehearsed at the other guys studio occasionally and he was telling people that we were gangsters and the studio was a money laundering operation with no customers. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. People liked the fact that the equipment was in the room, that we had a shop where they could get spares. They liked the fact that we had very cheap slots. They liked the old style rooms in converted lock up garages, because they got left alone to make music. They liked the fact that we would regularly organise gigs and events. They liked the fact that everyone was welcome, we didn't look down our noses at novices.

But the bottom line was that they liked the punk rock ethos of the studios, which was that it was a place where musicians could make music and feel like they were part of a family. Sure for some it was a bit too rough and ready, but when bands like The Beautiful South, The Damned and Amy Winehouse used us, we knew we were doing something right. We deliberately made all of the studios different sizes, shapes and sounds. Every artist had a favourite and every artist would have a different favourite. The Damned would only rehearse in Studio 7, Amy in studio nine. We became a massive part of the late 1990's hardcore metal scene, but we also had pop artists like Kate Nash and Modestep using us as their base. The rules were that customers are treated with respect and treat us and each other with respect. To this day, we have kept low prices and we still organise gigs for young artists.

It has been a difficult journey. Ernie succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 2002. He left a huge gap in the business. Our new, purpose built block coincided with the credit crunch, which hit every leisure business in the UK. It took a monumental effort to stay on track and stay solvent, but by the end of 2018, we were again doing well. We were looking to put up another block this year. Sadly Covid has killed our plans for growth and we are now in survival mode. As we employ 12 people, it is vital that we survive. When we reopened after lock down, our friends and customers flocked back to say how pleased they were we'd reopened. Many studios haven't survived and sadly more will go under. But today, I was chatting with a young band who have had ten rehearsals since we reopened. They don't normally chat, but they have a new, self released track out and wanted us to have a listen. They said that without us, they would simply be lost. I know where they are coming from. 2020 will be a devastating year for the music industry. All I can say is keep the faith and believe in what you are doing, because if you work hard enough and try hard enough, you will get to the promised land.

No comments:

Post a Comment